Thank you so much to the hundreds of monsters who have signed up since I started posting regularly on substack. As an independent artist with a giant mouth, your subscriptions help me do the work I want, unconstrained by collectors or corporations. I am truly grateful. It means the world.

If you like my art, you can also buy my books and prints.

My friend Brian Merchant (he of Blood in the Machine Luddite fame) recently published a haunting short story by Tim Maughan about what it might mean to bring iPhone production to America. The story had first been published by VICE, the hipster media brand that gave me my own start as a writer.

VICE was the first place to give me a chance as a writer. It was where I found my voice on personal essays, then cut my teeth as a journalist. They sent me to cover Guantánamo Bay and Abu Dhabi and Greek squats. It is no exaggeration to say this much maligned company changed my life. But like many digital Icaruses of the teens, VICE went bankrupt. Their website now a mass of broken links and missing images, where my best early writing sits entombed, like shades haunting some Hades of digital decay.

I want my favorite pieces to be read again.

So, for you monsters, I’ll periodically be republishing my favorite pieces from the VICE years. I’m going to start with the essay that was my breakout - Professional Naked Girl. I wrote this piece in 2012. Back then, (and perhaps still) a past in the naked girl industry was was supposed to preclude you from ever doing serious work again. I was just starting to make my name as a political artist, but my loyalties were to the bad girls who I came up with - the girls with stripper heels and chips on their shoulder bright as diamonds. I had no desire to hide or disclaim them. This piece, meant as a fuck you to respectability, ended up opening the door for me to become a writer. Here we are.

“If you keep traveling, you’re going to get yourself raped.”

Z. and I were sitting in a cafe on the edge of the Sahara. We’d been bumming around Morocco for three weeks. Despite my warnings, Z was increasingly disgusted with me for provoking constant street harassment. I covered myself chin to toe, but guys at the bus station would hiss at me like snakes anyway.

“That man just left a mosque,” Z said, after an elderly man eye-fucked me. “He’s supposed to be thinking of god.”

While picking ants out of our mint tea, we struck up a conversation with two other westerners. They were wind-burned, milk-wholesome Scandinavian girls. Z told me that he bet they never had guys stalking them around Marrakech.

“Marilyn Monroe could turn it on and off,” Z told me. “You can’t.”

Turning it on and off was something I thought about when I was lying naked in a warehouse in the Bronx, surrounded by hard-boiled eggs. The man photographing me adamantly denied having an egg fetish. After the shoot was over, he’d offer them to me to bring home and eat. I was broke enough to say yes.

I was 20. I’d been working as a naked model for two years. Back in the early aughts, there was a flourishing semi-legit business for girls like me, based off Craigslist and OneModelPlace. Girls too short, fat or plain to be legit models, unwilling to give the “fuck you” to convention it takes to be in legit porn, would pose for amateur photographers. We called them GWCs, or Guys with Cameras. They paid 100 bucks an hour.

We showed up in their hotel rooms. We posed on their beds. We told each other who was a good guy and who was a sociopath, knowing full well that if a GWC raped us, the police would do nil. A girl I knew was working as a bondage model. The photographer threatened to kill her. She wept. He let her go. When she went to the police, they shrugged her off. The photographer later murdered a model.

Surrounded by eggs and softboxes, I was doing my best to escape the trajectory of art school-retail-professional failure that, as a broke student at a bad school, I was marked out for. I wanted to make money fast, shove it into my business and then get out of here. I was young, which meant I had nothing to interest people with besides my looks. While those held out, I wanted to use them to get other, more versatile trading tokens.

My tits came in when I was 11. Guys hassled me ever since. My family isn’t one that sees no intermediary steps between early puberty and teen motherhood, but the Hasidic men who offered me 50 bucks for a handjob didn’t much care. Walking down Brighton Beach at 14, a 60-year-old Rodney Dangerfield lookalike asked me on a date. I declined. “No, a sex type date,” he said. When I declined again, he told me I was ugly anyway.

For every free coffee beauty privilege gets you, it also gets you a guy following you down the steps on the subway, saying he wants to work his tongue into your ass.

When men harrass us, they blame it on our looks.

A woman’s beauty is supposed to be her grand project and constant insecurity. We’re meant to shellac our lips with five different glosses, but always think we’re fat. Beauty is Zeno’s paradox. We should endlessly strive for it, but it’s not socially acceptable to admit we’re there. We can’t perceive it in ourselves. It belongs to the guy screaming “nice tits.”

Saying “I’m beautiful,” let alone charging for it, breaks the rules.

My art school roommate was a camgirl. She worked out of a cubicle, mechanically fucking a motorized dildo that the guy on the other side thought he controlled. She soon figured out more lucrative arrangements. I met her johns over a luxurious dinner, but sugarbabyhood wasn’t for me. Filet mignon didn’t taste like much in that company.

But her paycheck awed me.

I wanted to be an artist. Any tool to get there—even a website or properly printed portfolio—required more money than I could make working retail. If money drove me to the naked girl business, it was something else as well. I wanted to test myself. I wanted to see if I could work in a field fraught and stigmatized, and emerge unscathed. I wanted to burn off childhood.

So I went to Craigslist.

In the years since I was a naked girl, anti-trafficking activists have shut down the Craigslist adult services section. In typical anti-trafficking fashion, it accomplished nothing but irritating sex workers. The ads for webporn and used panties have migrated over to Talent, crowding out casting calls for no-budget movies.

Back then, we had an adult section. That was where I looked.

After answering dozens of postings—”Very Open Minded Models to shoot Erotica 4 Art-Exhibits,” “Highly Discreet”—I was hired to pose as a human statue at a loft party. Painted white like Venus, swilling absinthe with Manhattan’s monied demimonde, I made $250 cash, and swore off honest employment forever.

Being a professional naked girl would be Anaïs Nin-esque glamour, I thought, lying on velvet couches, smirking at convention. The first man who took my photo swept that all away. T met me in a coffee shop with what I can only describe as a binder full of naked women, all blinking and razor-burn and raw red knees; awkward human creatures that he proudly thought he’d made sexy. What I lacked in modesty, I made up for by being vain. My tits could be on the internet, but not my vulnerability. I posed for him anyway for a hundred bucks, arching my back till my muscles wept, after convincing him black and white film would make the photos “artistic.”

When I first took off my clothes for T, I thought the world would end. After a few times posing I kicked my dress away impatiently, indifferent to my skin.

If I was going to be naked, I didn’t want it to involve unflattering contortions in T’s living room. I took the best of his photos, jacked the contrast on my cracked photoshop, and put them on a website called One Model Place. OMP’s Floridian tackiness and dot-com pretensions went with its insistence that it was used by the fashion industry. It was not.

Soon my Hotmail pinged with offers. I went to hotel rooms thrice a week, shucking my clothes and speaking to the “photographers” with the careful mix of distance and friendliness that projected the fact that they would not be getting blowjobs.

It got better. I got better. I bought latex and bright lingerie from Strawberry’s, and sex shop platform shoes.

In each hotel room, I loved two things: painting my mask in the mirror, and letting my robe drop. I was a sleek machine for extracting money. Untouched.

The GWCs? Most were nice, if awkward. They had corporate jobs. They wanted to hire a naked girl up to their rooms, but feel like an artist doing it. The few who tried to touch me got barked at, kindergarten teacher style, and didn’t try again. Some got off insulting my body. One GWC, who was rich enough to have original Toulouse Lautrecs in the living room, berated my tits the whole shoot. “The model before you,” he said, “she had perfect breasts.” I took his $500, and recommended him, with warnings, to a friend. He insulted her too. “Your body is hideous,” he said, in an exact replay of what he had said to me. “Molly had perfect breasts”

When I was 21, I dropped out of school. Art school is a scam, a way to fit a blue-collar trade into an expensive collegiate format. But I also wanted to seize my window of professional naked-girlhood, to make as much money as possible while I was still young enough. By that time, I hated it. I came into each shoot expecting the GWC to rape me. If there’s a beauty privilege, there’s a good girl privilege too, where only virgins locked in their rooms are presumed innocent. By working in the sex industry, I had utterly thrown that out. Sex workers (like trans women) are believed to have brought violence on themselves. “Yes officer,” I imagined saying. “I was naked in his hotel room. For money.”

As protection, I had only the routine of making a guy comfortable while pouting through the baroque pantomime of a glamor mag. While driving me home from a shoot, one GWC begged me to fuck him. “My wife’s pregnant,” he says. “She won’t sleep with me. She says it will kill the baby.”

I stared ahead, willing him not to touch me until the road led us back to Brooklyn, where I could slam open the car door and run up the stairs to my apartment.

For safety, we were supposed to bring chaperones. I only did this once. My boyfriend came along to a Jersey hotel. The GWC had a a camera that shot hundreds of frames a minute. He was touchingly proud of it, like a man with a sportscar that he never took out of the garage.

My boyfriend sat against the wall, sketching, as I vamped in front of the vertical blinds. The GWC couldn’t get in the mood. “It’s not working,” he stuttered, passing me my hundreds. I used some of it to take my boyfriend to a cheap fish restaurant outside the Holland Tunnel. I wanted to vomit.

I was 22 years old and sweating on a gogo platform. Glitter melted into my cleavage. One fake eyelash hung off with clockwork orange precocity. In walked the guy I was dating. He was at the tail end of a relationship. He came in with his girlfriend, who was not a painted, exhausted, ridiculous professional naked girl.

I kept dancing, pretending not to notice.

At 4 AM, when my gig was over, I stood in my room. My body sang with pain. I slowly took off the fake hair, platforms, bustier, lashes. Each item I removed, more pain and tiredness leaked out.

The tangle of girl accouterments on my floor was almost as big as the girl.

Now, my hatred of posing baffles me. Professional naked-girl-dom was probably dangerous, often dumb. But it was $300 a pop, by generally complimentary men. Perhaps I had that artist’s entitlement. I was the one who should be making images, I thought, not selling mine.

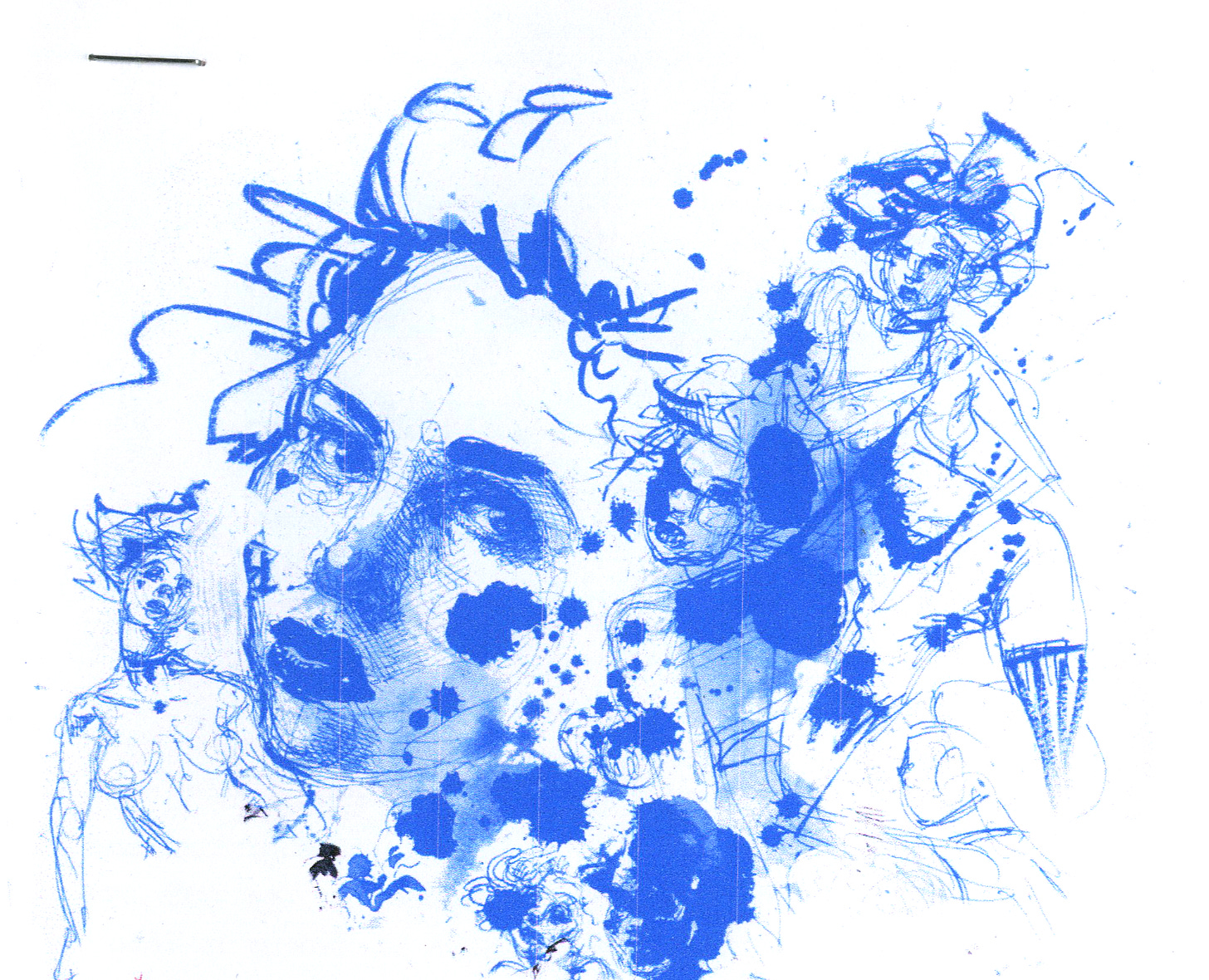

By the time I stopped posing, I had models of my own. God I love lovely women. Never have I seen a stripper without thinking she was a philosopher queen. If I sold my own image without much caring for it, I was addicted to theirs. It was the artist’s gaze that’s traditionally called male gaze but really isn’t. I wanted to paint their beauty, consume it.

Traditionally, this has been a raw deal for glittering girls. Hotness fades, but a painting is forever. You could make a gallery of history’s dolls, with Edie Sedgwick right at the top. Above it, you’d write “Muses Don’t Keep Copyright.”

Not that muses can’t be artists. I became friends with Amber Ray while dancing burlesque. I was awful. She was the best. Each night she’d perform alchemy on that dive bar stage. She’d be a lotus flower, a peacock, a golden god. She hired me to work with her as a promo model. We’d teeter around in wigs, corsets, 6-inch-glitter heels. By the end of the gig I’d be crying to sit down and itch my fake hair with a chopstick. “You’re the spirit of joy.” she’d hiss at me, looking magnificent. “SMILE.”

I was never much good at making myself my art.

When I was 23, I had enough art jobs to quit modeling. In quitting, I first got a look at how non-professionally naked women thought of their looks. It astounded me. Office workers lacerated themselves for not looking like Angelina Jolie, even though Jolie-hot Latina girls were bagging groceries throughout Brooklyn.

As a model, my looks were functional, a quantity to be squeezed and shellacked so as to sell for a higher price. Other women were hotter, but my face worked well enough. Civilian (as I thought of them) women baffled me by torturing themselves for a Hollywood beauty standard that would get them neither a better career nor better cock.

The naked girl business left me with an interesting lingerie collection and an ease with the camera’s insect eye. As planned, I saved my wadded up 20s, and used them to make myself an artist. Eventually, I became a well known one. Posing for magazines, I remembered the old lessons of self presentation. How I looked, which had been a harassment inducing burden, then a way to get cash, finally became my own.

Women’s looks are supposed to be our salvations. In a sense, mine were. But looks are an escape hatch to other places where they’re no longer as important. Beauty is powerful because it is pleasing. Real power means not having to please.

I remember stumbling onto this essay after donating to your Week In Hell Kickstarter. It was a bracing and powerful read then and now. I'm glad you're preserving it here, where more folks can find it, and share in your powerful insights into patriarchy, gender, labor, and the searing insect eye of the camera.

I still have Talking About My Abortion bookmarked, even though it's a broken-down page on a site that has mutated from what it once was. That piece means a lot to me. The decay and destruction of digital media is horrifying to me both personally and professionally (I actually am a librarian; many of my colleagues are on the front lines of preserving digital data and media). Seeing writers and artists like you, like Brian Merchant, republish and recirculate pieces is heartening, how we can all care for and support our shared digital ecosystem in the face of the degradation from capitalism and carelessness.